Back in 2014, when my Instagram was all photos of contortions with the Nashville filter (remember that?) and none of us had heard of Zoom, I wrote a series of blog posts called “‘Alignment Cues Decoded” for Yoga Journal. I was starting to see that most teacher training focuses more on memorizing sets of instructions than on understanding the purpose or intent of any given pose. It leaves instructors to deliver canned cues that neither they or their students understand. My goal with the blog was to explain the intention of these cues and offer adjustments.

These days, I’ve taken that thought process a few steps further. I don’t teach alignment cues anymore, since relying on them without offering options or adaptations/variations leads to a form of yoga that relies on hypermobility and is inaccessible to 80-90% of the population. In fact, this kind of teaching locks students into a performance-based mindset that directly opposes yoga’s central goal of helping us find our inner sense of worth, ease and understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

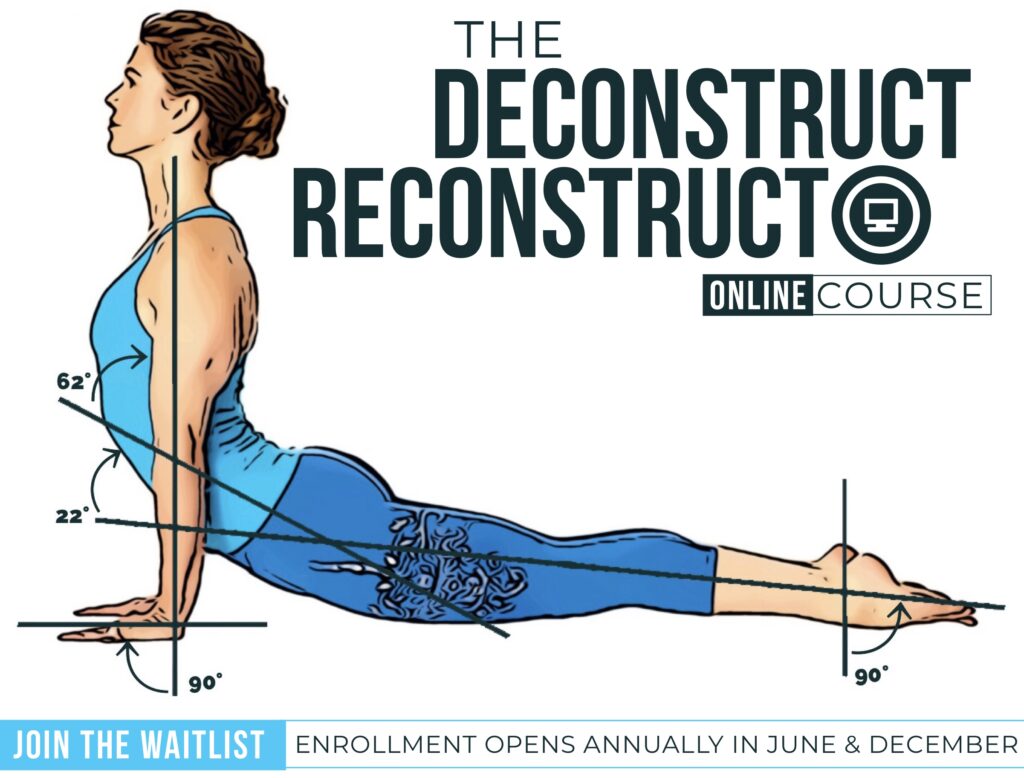

But there are still lessons to be learned from each pose. That’s why in my Deconstruct to Reconstruct course, I pull apart standard approaches to help teachers reconstruct their classes to be accessible and sustainable for all students.

One of the old blog posts for Yoga Journal that I’ve revisited focused on the cue “Wrist Creases Parallel.” At this point in my journey, I knew that this instruction didn’t work for me, or my students, and I explained that the focus shouldn’t be on those darn wrist creases, but on keeping the shoulders in an optimal position for weight-bearing poses, even if that meant shifting the hands.

My intentions in the Yoga Journal piece were good—but that piece didn’t go nearly far enough. Though I had advocated for a more flexible approach, I had not accounted for the range of variations in anatomy. And by arguing that hand placement was important for joint safety, I had made a dangerous over-simplification. Though my explanation was rooted in a desire to protect my students, black and white approaches just don’t work.

I explained that in gymnastics, hand placement was different than what was taught in yoga—but what I failed to mention is that hand placement in gymnastics is based on function, not a particular alignment. If the goal is to keep the back from torquing, different gymnasts may achieve that goal through different hand positions. That’s the message that should carry through to yoga.

For years I tried to help people adjust the way they approached the poses in small ways like tinkering with hand placement—now I take a more radical approach that completely reimagines poses to give students the option to find a variant that helps them reach the pose’s intent sustainably. After all, no hand placement will account for variance in people’s shoulders or skeletal proportions, and most people will never be able to safely perform certain poses.

And if we want to make yoga accessible to everyone, we need to face that offering small adjustments is not enough. By including hands-on-the-ground, weight-bearing poses in nearly every class, we are excluding a large number of students. I can make the current yoga model work better for a lot of people, but even different approaches to those poses do not make a class totally accessible if the poses remain the focus.

Instead, we need to reconsider what it is we’re trying to teach. Yoga is about non-striving, about not having to fix yourself, about letting go of the belief that we need to be more flexible or stronger to be okay or be loveable.

Focusing on achieving a certain pose is off-topic. Instead, can we work with what’s there and create an environment where people feel safe and comfortable doing things differently than each other?

If I ask a class to reach for a 7-foot-tall shelf by extending your arms above your heads with your elbows turned inward and your hand oriented in a certain way, very few people will be able to do it. If I say “do it any way you want without a stepstool,” a few more people might reach the shelf, but it will still be too tall for most. But what if I instead ask my students to reach up to the tallest surface they can safely and without help, in whatever way works best for them?

That’s the difference between exclusive and inclusive yoga.

And that’s my goal with Deconstruct to Reconstruct—promoting an approach to yoga that reduces harm and helps people find a sense of balance and a sense of self that doesn’t need to be fixed.

Want to learn more about how to apply this framework to your practice and teaching? Registration for Deconstruct to Reconstruct will reopen for enrollment in June. Add your name to the waiting list now.