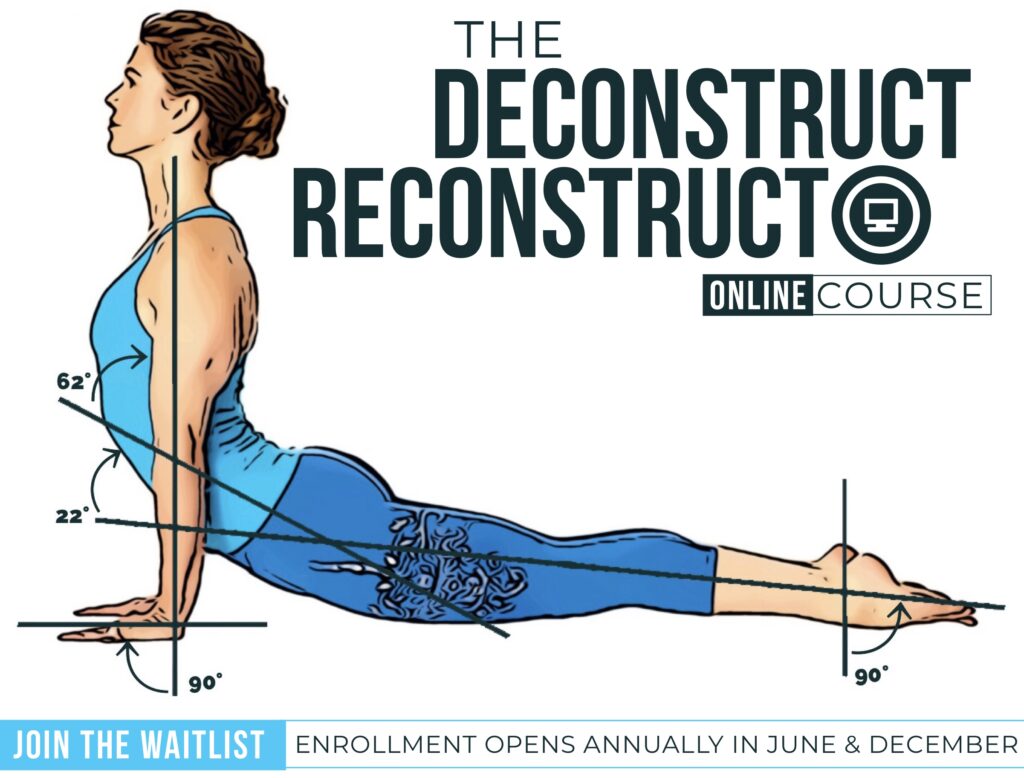

| Today I’m back with another dive into the “Alignment Cues Decoded” blog series I wrote for Yoga Journal around 2014/2015. Back then, I was early in my evolution as a yoga teacher—I could tell that students were struggling in cue-focused classes, but I still saw the inability to get into a particular pose as a challenge to be worked through rather than a fact of human physiology. My focus wasn’t on the pose’s intention, but on its physical expression. These days, I’ve flipped that script and work to make the benefits of yoga accessible to all, and teach others to do the same in their yoga classes through my Deconstruct to Reconstruct course. |

| So let’s unpack another of these “alignment” posts, this time on one of my favorite problematic poses, Bow Pose. Here’s the article in question. When I read this article today, the first thing that strikes me is how it’s built on the cycle of lack in yoga classes. I talked about the “tight and weak places that might be holding you back” as if there are simple “problems” that can be fixed to allow anyone to bend into Bow. Like so much of the competitive, commodified yoga we see all around us, this language leads us to believe that we are the problem. It preys upon peoples’ feeling that they aren’t enough and leads them to believe that if they just work harder or stretch further they’ll be able to fill that void. So much of our culture is based on marketing toward that sense of lack, toward selling us the thing that will make us whole. That’s not a belief system I buy into anymore. The article is also inherently flawed because this shape will never work for many people, no matter how hard they work at it. And others can add all of the stability work they want, but it still won’t be sustainable. Doing this pose without major shoulder or lumbar extension requires a very specific body type: a very short torso, short femurs, and very long arms. Otherwise, it requires extension that goes far past a clinically functional range of motion. Back then, I still bought into the idea that we could change our musculature to get past some of these challenges. Even when I was injured I believed that I could get back to doing these poses safely if I became safer or added stability drills. It just isn’t true. There’s nothing wrong with trying to get stronger, but strength alone won’t make poses accessible or sustainable on its own. I was trying to help students protect themselves, but my method was flawed. And isn’t it funny that I’m presenting this area for improvement, for adding something, when the message of yoga is that we already have all we need inside us? There’s no amount of glute strength that will make us more worthy of human connection and belonging and wholeness? Another thing that stands out to me is the rigidity of my approach. This piece was very much focused on achievement, of working toward the “full expression of the pose” (another phrase I despise). These days, I’d throw that aim out the window and instead offer students a series of explorations to see what different movements feel like in their body at that moment in time. Instead of climbing up a staircase, it’s about throwing the hierarchy out the window and helping students find what works for them. When I think about it now, most of these problems come back to the issue of power and agency in the class. As the teacher, I used to assume that agency and hold the keys (unintentionally, of course!), telling students what to do and what was “right” without giving them time to explore. Instead, we need to give students the tools and information they need to make choices from a place of full personal agency. If this is something you’re interested in learning how to do, that’s exactly what my Deconstruct to Reconstruct course teaches you. We pull apart standard approaches to help teachers reconstruct their classes to be accessible and sustainable for all students. Interested in learning more? |