How has your understanding of yoga changed in the last five years? I’ve been digging back into a series of “‘Alignment Cues Decoded” blog series I wrote for Yoga Journal around 2014, and boy is there a lot to unpack. Back then, I knew that yoga pose alignment cues were poorly taught and didn’t help students—but I still believed that yoga was accessible to most with small adjustments. Now that I know that no tweaks can overcome individual variation in anatomy and skeletal mobility, I can see that these posts completely missed the point—that our approach to yoga needs to be fundamentally changed for true accessibility. This kind of close examination is exactly what my Deconstruct to Reconstruct course is all about.

Today, I’m looking at a real doozy of a yoga pose alignment cue—”Soften Your Front Ribs,” about a cue that’s primarily related to correcting alignment in postures as it relates to “keeping the lower back safe”. I now see that despite the anatomical information being correct in relation to reducing lumbar extension and the likelihood that the issue is happening from not just the thoracic region but largely from pelvic placement, this piece contains a fundamental flaw. It assumes that people need to be fixed and it oversimplifies the extremely complex causes of back pain and injury. Ironically, my own efforts to “fix” these perceived issues in myself contributed to the development of my real back problems.

When I wrote this article, I thought that adjusting the language used to describe the cue and allowing for a little more variation would help students prevent injury. And I’ll stand by the argument I made in Yoga Journal that the phrase “soften your front ribs” is just plain weird. What does that even mean? How do you soften bones? This wording doesn’t work for the literal among us. But I had yet to realize that it wasn’t the language that needed to change, but the beliefs underlying it.

For example, we are led to believe that having a visibly rounded upper back or arched lower back is a problem that needs to be changed—even if the person is experiencing no pain. But we can’t see the underlying factors that our body has adapted to address. Often, by trying to correct a superficial issue, we actually make things worse. Our obsession with posture is primarily aesthetic.

In fact, common ideas about back problems are based on beliefs that are not supported by science. I used to fall into the trap of believing that “weak upper backs” were a common problem. But if we are able to walk and move through space, to pick things up, to lift objects, to get up off our bellies if we’re laying down, then our upper backs aren’t weak. They may not have the requisite strength it would take to let’s say do back extensions at the gym with a 30 lbs weight, but that doesn’t mean they’re weak. Strength can only be measured relative to specific tasks.

If there is a true imbalance, that’s far outside the scope of anything that can be addressed with yoga alone. And no amount of yoga will prevent the rounding that some experience while aging—that’s pure genetics. Once again, this construction creates a false problem to “fix.” The same goes for the core. Studies have shown that the idea that core stability staves off back problems is pure myth. No amount of muscle activation or strength training can prevent or heal back injuries or pain.

And some components of posture have nothing to do with sitting too much or weak muscles—they’re just the way our bodies are shaped, not something that can be changed by a yoga pose. I have a large natural lumbar curve, always have and it didn’t bother me one bit, and was taught to “fix” that by tucking my butt under me. But that caused me to put excess pressure on my SI joints. Instead of fixing a problem that didn’t exist, I created a real one.

In this Yoga Journal article, I blamed posture “issues” and “weaknesses” on time spent sitting at desks and in cars. But that belief is based on a perfectionistic, fear-based view that comes dangerously close to treating sitting like a character flaw. And it just doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. In actuality, sitting often causes problems not because of the position but because of the stress we experience while sitting at our desks worrying about our jobs or sitting in a car navigating traffic and that we don’t spend enough time doing things like relaxing deeply or enjoying activities that soothe and nourish us and balance out excess stress.

In my own practice and teaching, I’ve found that the energetic and stress components of modern life are best addressed through relaxation, not contortion. When given the chance to truly relax our bodies will often reset to the posture that best suits us without any conscious action. Any of you that have taken a restoratives or hypermobility workshop with me will know that from the before and after assessments we use to demonstrate this very point. Superficially addressing aesthetic posture without addressing internal factors is counterproductive. Our bodies have a lot going on below the surface.

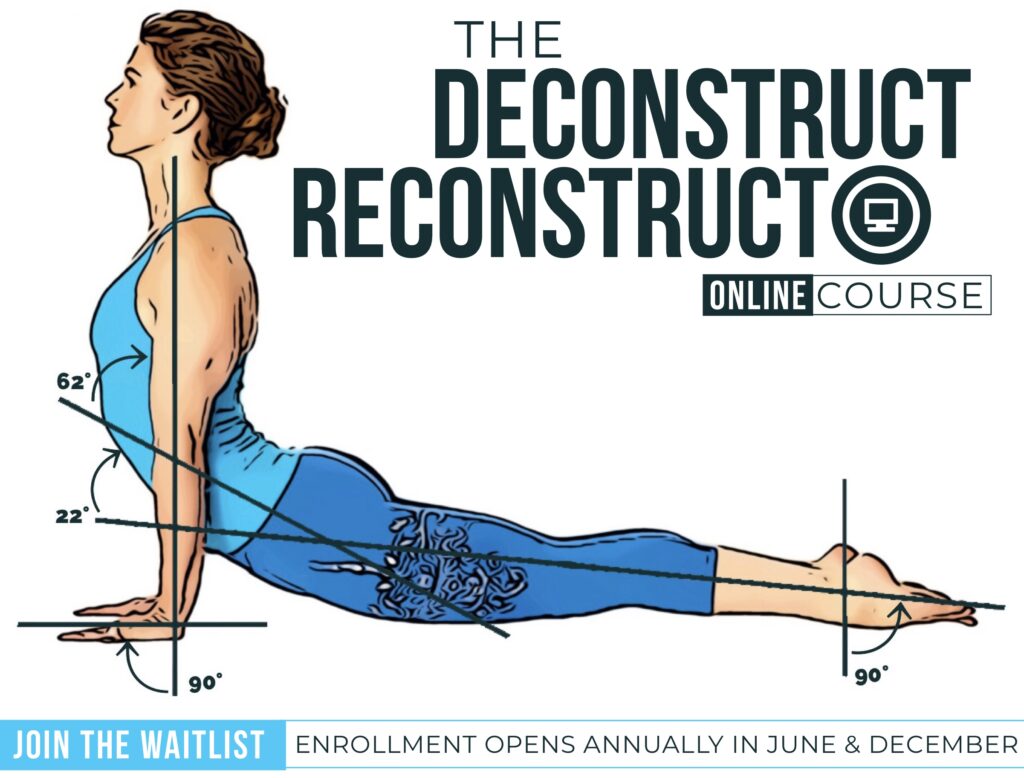

Ultimately, this Yoga Journal article is problematic because it assumes that there is a universally correct posture that can be assessed externally in yoga pose and visually or by a set of “correct” angles for the human body. That couldn’t be farther from the truth, and approaching yoga teaching with this assumption is dangerous. If we use externally focused alignment cues to force students to move their bodies in an unnatural way, rather than addressing what is actually going on in our bodies below the surface, we simply cause additional stress.

These days, I would say that while we can’t mitigate all harm, we can vastly reduce the physical harm caused by yoga asana classes through adapting the task itself. Not just by changing how we verbalize our cues, or by adding muscle activation or strength training. Instead of focusing on external form, we must identify the aim we intend a posture to serve that day and work with each of our students to find the variation that works for them and fits them rather than harms them.